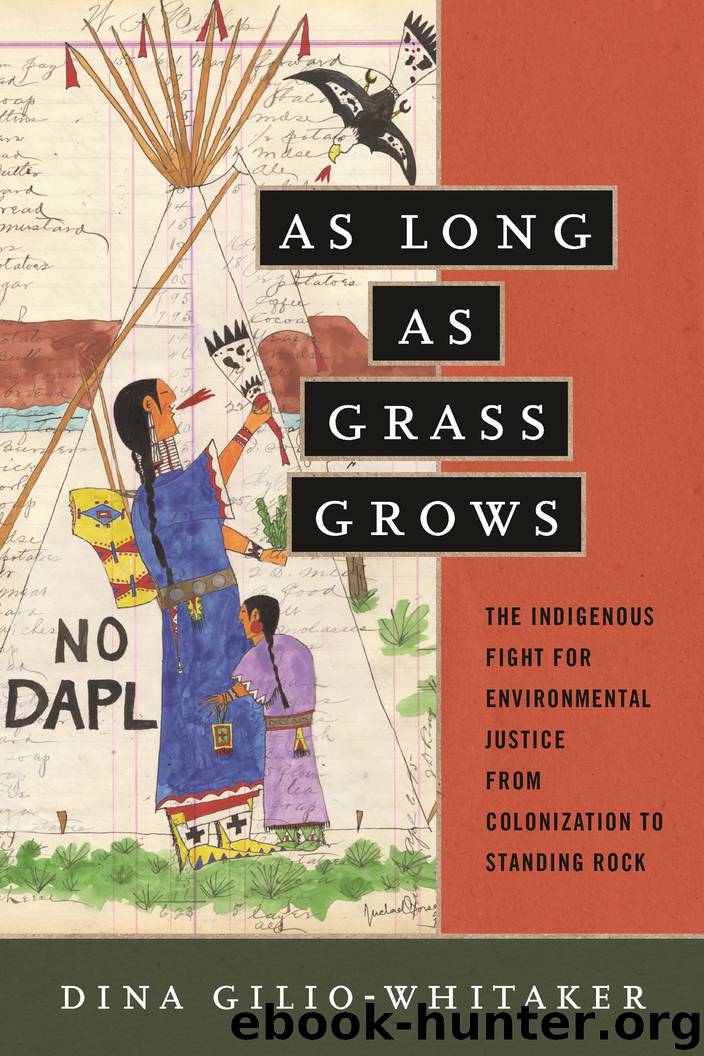

As Long as Grass Grows by Dina Gilio-Whitaker

Author:Dina Gilio-Whitaker

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Beacon Press

WORKING TOWARD PRODUCTIVE PARTNERSHIPS

A milestone in the environmental movement occurred in 1992 with the convening of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, also known as the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit. The Rio Summit was, among other things, the world’s governments formal acknowledgment of climate change and resulted in several binding agreements, including the Framework Convention on Climate Change. By then, Indigenous peoples had been organizing around environmental issues at the international level since at least 1972, when a delegation of Hopi and Navajo activists attended the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, the United Nation’s first major international conference on the environment.35 Climate change agreements like the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Accords eventually followed, and by 2000 a robust climate justice movement was mobilized. On a large scale, climate change activism married the environmental movement—which had morphed into one wing of an international nonprofit industrial complex—with grassroots activism. It signaled that environmental justice was a global but distinct aspect of the environmental movement, since the detrimental effects of climate change were unevenly distributed between the so-called developed and undeveloped worlds. Whereas the environmental movement writ large was concerned with the myriad ways humans were causing environmental degradation, climate change, caused by greenhouse gases produced primarily by burning fossil fuels, pinpointed the blame on Big Oil and its far too cozy relationship with governments. But Indigenous and fourth world people were on the frontlines of climate change, as people living in closer relationships to the Earth felt its impacts first: loss of land due to sea level rise, desertification, drought, disruptions to subsistence-based food systems, intensifying storms, loss of sea ice, and a host of related ecosystem changes. Yet they had been largely excluded from United Nations climate change talks, and worse, the Kyoto Protocol’s creation of a market-based system of carbon trading exposed Indigenous peoples to new abuses by States. It was thus natural that Indigenous peoples would rise as global leaders of the climate justice movement.

During the 1990s new kinds of stories began to appear in American environmental literature and media, conceding the ways the environmental movement had marginalized and alienated Native peoples. New alliances between tribal nations and people with whom they had historical enmities (not just environmental groups) increasingly formed to oppose environmentally destructive development. Indigenous environmental groups sprang up, like the Indigenous Environmental Network (1990), Honor the Earth (1993), and other locally based tribal and non-Native coalitions, such as the Shundahai Network (a Shoshone effort to resist the Nevada Nuclear Test Site), the Environmentally Concerned Citizens of Lakeland Areas (Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe citizens’ opposition to a sulfide mine in Wisconsin), Sweetgrass Hills Protective Association (multiple tribes aligned with non-Natives to fight a gold mining operation in northern Montana), to name just a few. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, with the oil industry posting record profits, proliferating fracking operations,36 and massive new pipelines planned—exacerbating tensions created by the 2008 recession and skyrocketing wealth inequality—public fury grew.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32549)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31948)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31932)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31918)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19037)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15965)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14489)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14061)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13950)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13351)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13351)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13233)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9326)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9280)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7497)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7307)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6747)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6613)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6267)